Over the past few weeks, I have been thoroughly reviewing the burial registers of Tilburg. Not because I was looking for additional information about my own family members, many of whom came from this city in the Dutch province of Noord-Brabant. No, I wanted to get to know these registers better. Burial registers are often dismissed as dull, as a source lacking useful details. Yet, if you systematically go through these lists, you sometimes come across interesting entries. I will mention a few below.

Genealogical source

Whether burial registers contain a lot or a little detail, they are of undeniable importance to genealogical research. Every ancestor was born and died at some point. To determine when birth (or baptism) and death (or burial) occurred, either civil records or the DTB registers are the preferred source of information. Research into ancestors from before 1811 is primarily conducted through the DTB registers. The abbreviation DTB stands for Dopen (baptisms), Trouwen (marriages), and Begraven (burials). These registers are often also called parish registers. That term is fine in itself if the registers were compiled by a religious denomination (whether Catholic, Protestant, or otherwise). But there were also registers compiled not by a religious denomination, but by civil authorities. These are, for example, marriage registers from the court of aldermen, the schepenbank.

View of the market square in Tilburg with the church and cemetery in the background. (Jan de Beijer, 1742. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

Burial registers

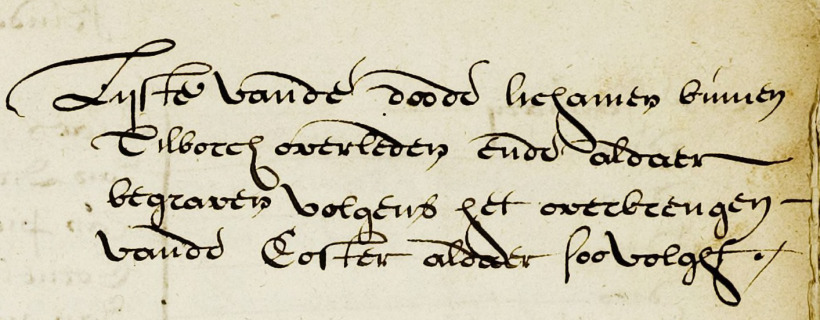

In this article, I will limit myself to the burial registers of Tilburg, which were compiled in the 17th and 18th centuries by the sexton of the (then only) parish church in the city. The sexton was employed by the Dutch Reformed Church, which had also ‘taken over’ the local church building from the original Catholic parishioners. There are two types of lists containing information about burials. On the one hand, there are lists in which the sexton recorded who was buried in the church and for whom the church bells were rung. Maintaining these lists was of great importance to the sexton: he received additional income for this type of work. On the other hand, there are lists or registers that show all persons buried in Tilburg (both in the church and in the churchyard).

Content

Burial registers often do not contain much information. For this reason, many researchers classify them as “very boring.” And to a certain extent, that is true. A standard entry in these registers contains little more than the name of the deceased and the date of the burial. (Details about the date of death are usually missing.) Moreover, the name of the deceased is often not very detailed either: an entry might simply state “the wife of Hendrik Maas.” However, there are also registers that provide a bit more detail. For example, whether the deceased left behind any children or parents, and where the deceased lived (in which neighborhood). This already makes research in these registers more interesting. In exceptional cases, it is also noted that an additional fee was paid for the burial. Below, I provide an example of such a standard entry.

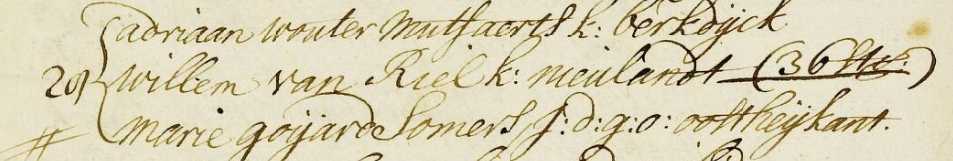

Entries from 28 March 1732, as found in the Tilburg burial register for the period 1732–1746. (Collection 15, item 31, image 2. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

On 28 March 1732, three people were buried in Tilburg: Adriaan Mutsaerts, Willem van Riel, and Marie Somers. The entries provide some additional details. First, Adriaan and Marie have a patronymic listed: Adriaan was a son of Wouter, Marie was a daughter of Goijard. This is very helpful for further research. All three have letters indicating their marital status. The ‘k:’ stands for ‘kinderen,’ meaning that the person had children (and thus, most likely, married). The letters ‘j:d:g:o:’ are an abbreviation for ‘jonge dochter, geen ouders,’ meaning that the person was unmarried and no longer had parents. All three also list their places of residence: Berkdijk, Nieuwland, and Oost-Heikant. Finally, Willem van Riel’s records indicate that a sum of 36 stuivers was paid for additional services at the funeral. Occasionally, “avond” was mentioned. This mainly occurred when very young children were buried, in the evening without any form of funeral service or ceremony.

Notable deaths

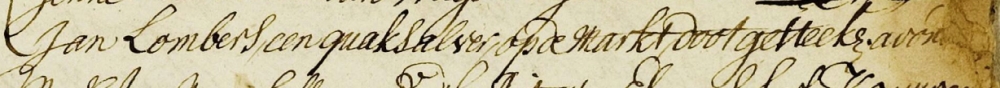

Anyone who systematically examines these burial registers – that is, looking at the entries one by one – will come across many interesting facts. For some, the details of how the deceased met their end are mentioned. For example, there were residents of Tilburg who drowned or were stabbed or beaten to death. An example of such a latter case was Jan Lombers, who was buried on 20 April 1734. His annotation reads: “a quack stabbed to death on the Market Square.” He, too, was buried quietly in the evening.

Entry from 20 April 1734, as found in the Tilburg burial register for the period 1732–1746. (Collection 15, item 31, image 13. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

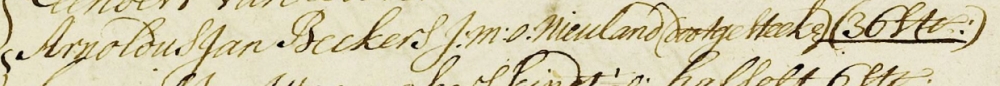

A similar fate befell Arnoldus, the unmarried son of Jan Beckers from Nieuwland. He too was “stabbed to death.” His funeral took place in Tilburg on 11 June 1734.

Entry from 11 June 1734, as found in the Tilburg burial register for the period 1732–1746. (Collection 15, item 31, image 14. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

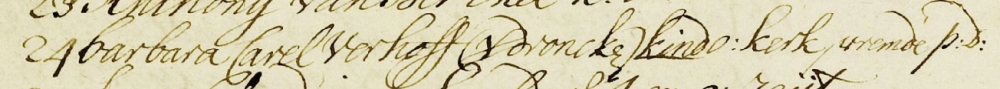

The year 1734 was one of unusual deaths in Tilburg. Less than two weeks after Arnoldus Beckers, Barbara was buried. She was the daughter of Carel Verhoff, and according to the burial register, she had drowned.

Entry from 24 June 1734, as found in the Tilburg burial register for the period 1732–1746. (Collection 15, item 31, image 14. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

Big news

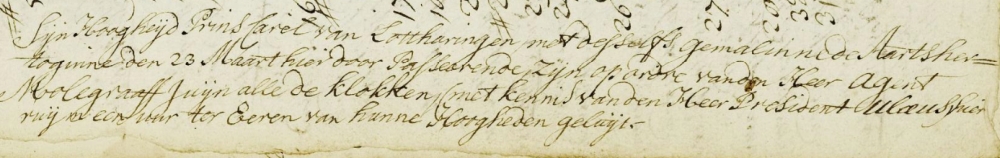

The sexton’s burial registers in Tilburg also mention other events, which were less related to individual residents and more to “big news.” For example, the sexton noted several times that he rang the church bells because dignitaries were visiting or passing through the city. On 23 March 1744 it was Charles of Lorraine and his wife who passed through the city on their way to Brussels. For an hour the sexton rang all the bells in the church tower.

Comments written next to the entries from March 1744, as found in the Tilburg burial register for the period 1732–1746. (Collection 15, item 31, image 60. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

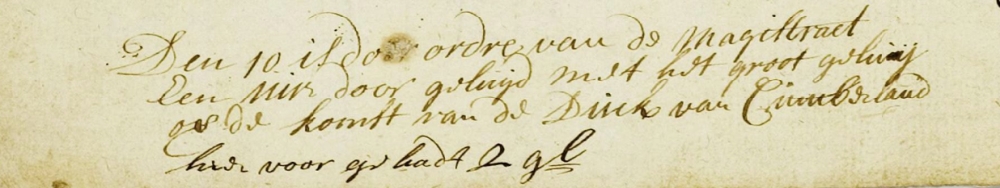

Three years later, on 10 April 1747, the Duke of Cumberland came to Tilburg. Once again, the sexton rang the bells for an hour. He was paid 2 guilders for this. Ironically, the sexton made an amusing, yet also embarrassing, slip of the tongue: he called this high-ranking visitor not the “duke” but the “duck” of Cumberland. Well, the sexton must not have been fluent in English!

Comments written next to the entries from April 1747, as found in the Tilburg burial register for the period 1747–1752. (Collection 15, item 32, image 3. Credits: Tilburg Regional Archives)

Final words

These are just a few examples of interesting entries in the burial registers recorded by the sexton of Tilburg in the mid-18th century. Many more can be found in these lists, or in other registers from Tilburg or elsewhere. Perhaps these examples will inspire other researchers to take a closer look at what other interesting facts the burial registers reveal, beyond the essential mention of the death of an ancestor or relative. These sources unintentionally shed new light on local history.

Have you also done research in burial registers and found any special mentions? Please let me know in the comments section below this article.